Learn from the best.

by Lea Brayton

Students at Montana State hail from far and wide, gathering under the Big Sky to learn from decorated faculty whose achievements, research, and talents are tough to beat. Don’t miss the chance to study under one of these memorable mentors this year.

William Wyckoff—Professor of Geography, Earth Sciences

According to Wyckoff, landscapes are great teachers—and he would know, as he wrote the book on it. His latest publication, How to Read the American West: A Field Guide, focuses on the changing geography of the West. His philosophy stresses that people and place are cohesive, jointly transforming their environment. In his newest project, he follows the footsteps of Arizona state employee Norman Wallace to recreate landscape images from over 70 years ago.

Wyckoff is known for clarity of presentation and his articulate, passionate rhetoric. Kyla Jewel, junior at MSU, says his class was one of her most memorable: “Geography’s not always the most thrilling subject, but I liked that Professor Wyckoff was always enthusiastic about the material and that translated to the whole class.”

Wyckoff’s professorship is one to admire. He inspires true educational growth, teaching that “Learning about geography should ultimately take you out of your classroom, beyond your computer, even away from your books, and into the larger world which tends to be much more complicated, interesting, and unpredictable.”

Whitney Hinshaw—Director of Group Exercise, Recreational Sports & Fitness

Athlete, coach, instructor, and director Whitney Hinshaw has always been involved in the world of athletics. With a dietetics degree giving her a strong health background and a master’s in higher education, Hinshaw is one of the lucky few who have successfully coupled passion and profession.

Relatively new to MSU, Hinshaw is focused and encourages her students to move outside their comfort zones. Her courses are informative and instructive; her stories of her own competitive experiences often relatable and humorous; and her spin classes likely to be difficult and invigorating. As an educator, she believes in something she calls transferable heart skills, which her wellness philosophy explains: “If you can train heart and mind for a trail race, you can train for anything educational, professional, etc. It’s all the same skillset. Training requires grit, persistence, discipline, self-control, and emotional intelligence—so does preparing for the professional world.”

Hinshaw is working toward her own personal goal of “50 by 50”—completing a half-marathon or similar competition in every state by age 50 (she’s currently in her 20s). So far she has seven states checked off. Run at the chance to learn and train with her this year.

Selena Ahmed—Assistant Professor, Health & Human Development

With 17 different courses on record and teaching experience at six major universities, Montana State’s powerful “rising star” Selena Ahmed is bringing much-deserved attention to the Sustainable Food and Bioenergy Systems (SFBS) program. Her complex research looks at variations in agro-ecosystems—such as economic, environmental, and human factors—to discover better management practices and more sustainable solutions.

Ahmed is a big-time contributor to MSU’s research community, and she’s continuously heading up groundbreaking global projects. She has spearheaded research in nine countries and is distinguished for her work examining tea production, which she calls “a diverse and elegant system.” She’s currently studying local food choices in on the Flathead Reservation and the Tibetan Plateau.

Working closely with students, Ahmed encourages collaboration across disciplines and involvement in research. Recent SFBS graduate, Cory Babb, remembers the opportunity: “Her class was my first chance to actually take part in publishing research.” Keep an eye out for this inspiring intellectual on campus this year.

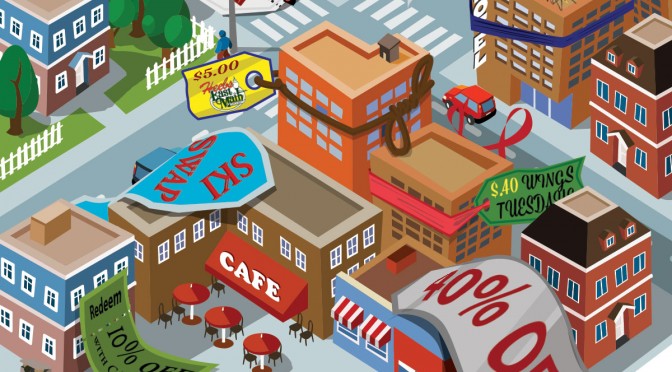

Imagine rack upon rack of top-of-the-line brands, all at significant discount—at

Imagine rack upon rack of top-of-the-line brands, all at significant discount—at

For higher-quality items at prices well below retail, head out W. Main, just past 19th. The

For higher-quality items at prices well below retail, head out W. Main, just past 19th. The